This year I volunteered, as I have done for some years, to participate in the Passion reading at the Palm Sunday service at Grace Church. Last year I was Narrator (effectively St. Mark, from whose gospel the reading was taken), which meant I had more lines than anyone else. This year the reading was taken from Luke, and I was given the role of Pontius Pilate.

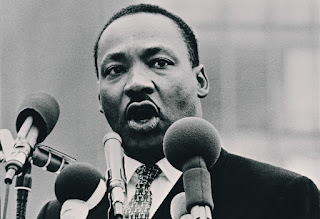

"Not the most appealing of characters," I thought. At least I had more than one or two lines. This got me to thinking about the enigmatic character of Pilate. The image above, by

Giotto de Bondone (1266-1337), shows him looking devious--note the averted eyes--but also weak, as indicated by his soft, fleshy features. No one who didn't see Pilate in the flesh knows what he looked like; there are no surviving portraits, drawings, or sculptures from life, if indeed any ever were made. Giotto's fresco comports with the accounts in the gospels, which describe Pilate as vacillating, initially appearing to sympathize with Jesus, although willing to have him flogged before releasing him, but later yielding to the demands of the crowd and ordering him crucified.

To most contemporary Christians that yielding and that order cements Pilate's characterization as a Very Bad Guy. I remembered, though, having read that Coptic Christians in Africa consider him a saint. The

Biblical Archaeology Society gives an account of how this came to be.

St. Augustine of Hippo, an African, believed Pilate to have been a convert to Christianity. Pilate's washing of his hands and declaring himself "innocent of this man's blood" (Matthew 27:24) is seen as a parallel to Jesus' sacrifice washing away the sins of humanity. Pilate's wife was also canonized in the African and Greek Orthodox churches on the basis of her message to Pilate, reported in Matthew 27:19, that he should not harm Jesus because "I have suffered a great deal because of a dream about him."

Some biblical scholars have argued that the quasi-sympathetic portrayal of Pilate in the gospels is a result of the gospel authors' seeking to shift the blame for Jesus' crucifixion from Roman authority to the Jews. This was because, at the time the gospels were written, Christianity, which initially had been a sect within Judaism, was beginning to separate itself from its Jewish origin and was seeking Roman approval, or at least a measure of tolerance. The starkest indication of this is in Matthew 27:24-25, where Pilate washes his hands, declares his innocence, and gets the response, "His blood is on us and on our children." For many centuries, it was Christian doctrine that the "us" in that statement meant all of the Jewish people, at least apart from the few who were Jesus' disciples or followers. This was the basis for many centuries' persecution of Jews in pogroms and ultimately in the Holocaust, although the latter also had non-religious origins. On October 28, 1965 Pope Paul VI promulgated

Nostra aetate ("In Our Times"), a declaration of the Second Vatican Council that the Jewish people as a whole, including all Jews living since the time of Jesus, were innocent of Jesus' death.

The vilification of Pilate appears to have begun with the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, and a concomitant desire to break with Rome's earlier paganism, to which Pilate bore allegiance. It has been years since I read (in translation) Dante's

Inferno, and I was curious to recall where in the circles of hell the poet placed Pilate. As it turns out, Dante nowhere mentions Pilate by name in the

Inferno, or anywhere else in the

Divine Comedy except in Canto XX of

Purgatorio, where Dante calls Phillip IV of France "the new Pilate" for his having delivered Pope Boniface VIII to his enemies. There is an ambiguous reference in

Inferno Canto III, where Dante sees the vestibule of hell to which the uncommitted--those who did not choose between good and evil--are condemned. Here he sees "the shadow of that man who out of cowardice made the great refusal." Some readers have interpreted this to refer to Pilate, whose "great refusal" was not to defy the crowd's demands to crucify Jesus. Others think it refers to Pope Celestine V, whose abdication of the Papacy led to the accession of Boniface VIII (the same mentioned in

Purgatorio XX), whose policies led to Dante's being exiled from his native Florence.

Consideration of Pilate's nature brought me to an uncomfortable realization. In

an earlier post, I noted that the then Episcopal Bishop of Alabama had joined other prominent local Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish clergy in calling on Dr. Martin Luther King, then jailed in Birmingham, to call off the peaceful demonstrations against segregation and for civil rights that he led. Reading that letter, with its calls for moderation and patience, I realized that, had I been in the position of that bishop at that time, I would have been strongly tempted to sign the letter. While my heart was on the side of those demonstrating for justice, my inclination has always been to avoid confrontation where possible, and not to alienate those in power, in the hope that in time they can be persuaded to do the right thing. What would I have done had I been in Pilate's position? Could I have mustered the courage to defy the crowd? Can I find that courage now?

Addendum: see

John Wirenius on Pilate.